https://iclfi.org/spartacist/en/69/electoral

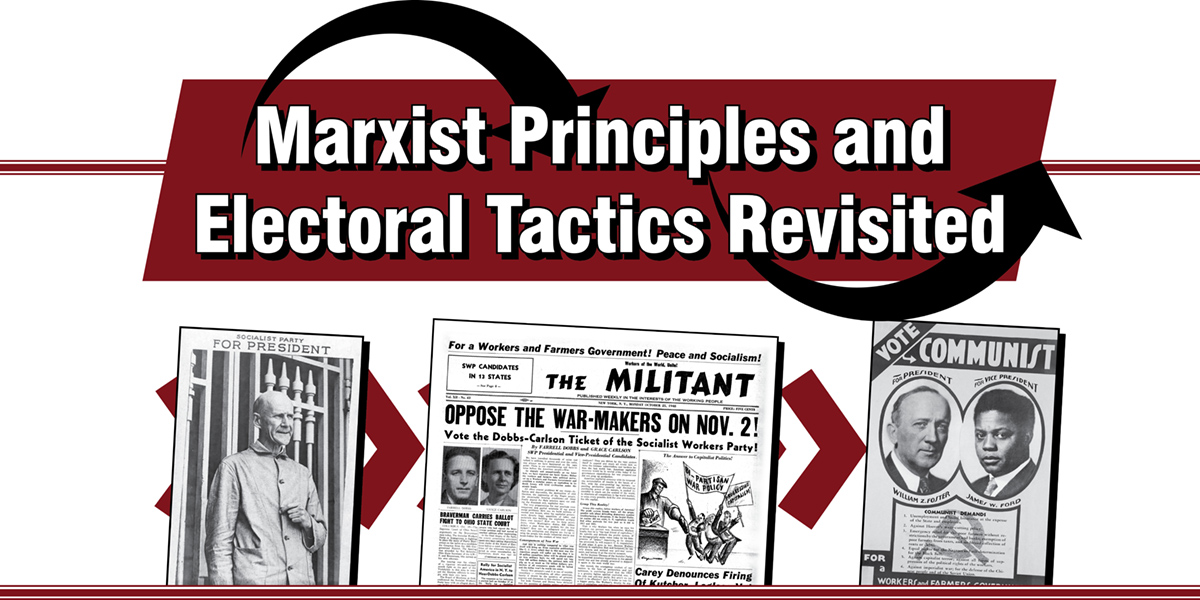

In March, the ICL International Executive Committee (IEC) voted to correct the position we took in 2007 that it was unprincipled for Marxists to both participate in elections for executive offices in capitalist governments and to take such offices. Repudiating the article “Marxist Principles and Electoral Tactics” (Spartacist English edition No. 61, Spring 2009), the IEC motion stressed that contesting executive offices was necessary for “breaking the illusions of the working class in bourgeois democracy, strengthening the class struggle against the bourgeoisie and advancing the fight for proletarian power.”

Printed below is a document by Vincent David that provided the basis for the motion. It has been edited for Spartacist, with a slight addition based on discussion at the IEC meeting. We dedicate it to the memory of Ed Kartsen (1953-2023) and Marjorie Stamberg (1944-2024), who fought for communism in bourgeois elections and beyond.

The year 2024 will see a record number of national elections taking place. As the decline of U.S. hegemony brings increased turmoil and instability, all these elections will reflect growing polarization and deep social discontent and will see the participation and, in some cases, likely victory of open challengers to the liberal status quo of the last decades, mainly from the populist right. The increased political activity offered by the election periods gives us an opportunity to propagate our ideas and advance the struggle to build a Marxist pole against the defenders of the brittle liberal order and its reactionary opponents. To do so properly, the ICL must first rid itself of the leftovers of the sectarian and doctrinaire method saddling us in this field.

Many comrades have argued that the article “Marxist Principles and Electoral Tactics” is wrong. Indeed, it is. But it is one thing to say so and to collect quotes from Engels, Lenin and the Comintern to expose how false its various arguments are. It is another to properly attack its entire method and counterpose another method—a Marxist one.

The task of the proletarian revolution regarding bourgeois democracy was clarified by our movement long ago. Bourgeois democracy is a facade for the rule of capital, which must be replaced by workers democracy (soviets), together with the replacement of the capitalist state machinery by the dictatorship of the proletariat. But the mass of politically advanced workers in various countries still has illusions in bourgeois democracy. Such illusions vary from the belief that electing pro-working-class politicians can advance workers’ conditions to thinking that socialism can be achieved by parliamentary means. Therefore, the central question for communists is how to break such illusions. Any discussion about our approach to elections that does not start from this point is meaningless chatter.

And that is precisely what the Spartacist article is. Its approach to executive posts and elections has nothing to do with fighting illusions in bourgeois democracy. Despite acknowledging how widespread they are, the article proposes absolutely nothing to combat them apart from abstract propaganda and the false answer of abstaining from participation in elections to executive offices. The peg of this article was to repudiate the ICL’s former position that communists could run for executive offices provided that they declare they would not take such posts. But that position, too, had nothing to do with the main point: how to break illusions in the capitalist state and parliamentarism. Both positions, and crucially the method behind them, are classic examples of formalistic thinking and scholasticism completely alien to Marxism.

Scholasticism vs. Marxism

The method of the Spartacist article consists in propagating abstract Marxist principles and evaluating political positions on this basis, totally divorced from the living struggles of the masses and the bourgeois illusions they hold. This idealist gymnastics is supported with a vast array of past Marxist writings, employed not as a guide to action but as timeless scripture.

Everything is considered in a void, with each new proclaimed “extension” of the work of the Communist International only succeeding in removing ourselves further from the realities and struggles of the working class. This is because the main concern driving this method is not the struggle for leadership of the masses but the quest to find a talisman which can prevent potential opportunism on our part. The logic is: if you don’t want to drown, don’t get into the water.

A problem in the discussion up to now has been to criticize the Spartacist article simply on a theoretical level, showing how its account of the history of the Marxist movement on this question was false and counterposing what the Comintern and Lenin actually said. The effect has been to repeat Marxist principles but put aside the key question, which is how to fight for them. In the process, many comrades have gotten lost in particular historical or theoretical arguments and speculation about this or that situation without exposing the article’s anti-Marxist method.

In contrast, the Marxist method consists in approaching each question from the standpoint of advancing the class struggle toward proletarian revolution. Marxist principles must be applied concretely. Strategy and tactics must be based on the objective interests of the working class, starting from its actual experience and always going back to it, in order to attack its existing illusions and its current leadership. Revolutionary leadership consists not in upholding fixed principles or past writings but in the capacity of the vanguard to wield principles to guide the working class through events, distilling their lessons and putting forward a path of struggle corresponding to the current conjuncture and advancing the workers’ interests.

It is with this framework that we must approach the question of elections, and of executive posts more particularly. In the real world, and not in the imaginary fiction of formalists for whom principles float in the void, the vast majority of workers still cling to bourgeois democracy. Those who might come to accept the necessity of attacking bourgeois property or even expropriating the capitalist class want to know why it is not possible to do so through the executive posts of the capitalist state and through bourgeois-democratic means.

They will not come over to our view simply through theoretical arguments over the class character of the state and democracy. Rather, they want and need to test things in living reality, through practical experience. A revolutionary organization aspiring to become more than a tiny discussion group must be ready and willing to accompany the workers in this process, not by sharing their illusions but by helping them come to the conclusion that bourgeois democracy stands as a guardian of the rule of capital and that they need their own organs of class rule.

It is impossible to guide the working class and shatter its illusions in bourgeois democracy if we remove ourselves from the electoral contest. To demonstrate how parliamentarism is a tool of deception which must be replaced by workers democracy, we must be within parliament. Communists work in that arena to unmask the hypocrisy of parliamentarism, the bourgeoisie and the labor lackeys, seeking to demonstrate and exacerbate the inevitable opposition between the burning needs of the masses and the obstacle that parliamentarism erects on the way to their resolution. As Lenin argued against the ultraleftists:

“Whilst you lack the strength to do away with bourgeois parliaments and every other type of reactionary institution, you must work within them because it is there that you will still find workers who are duped by the priests and stultified by the conditions of rural life; otherwise you risk turning into nothing but windbags.”

—“Left-Wing” Communism—An Infantile Disorder (1920)

The same method applies to executive posts. There exist profound illusions among working people of all countries in the possibility of achieving radical change—even socialist transformation—through control of the capitalist state, whether on a national or a municipal level. Whatever we may wish, it is almost a law of history that the sharp social and political crises that will impel the proletarian masses into struggle will also push them to try to “lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes” (Karl Marx, The Civil War in France, 1871).

The role of revolutionaries is not to stand aside and denounce such enterprises as unprincipled but to guide the workers through such experience. That does not mean to tail them but to make use of every crisis to facilitate their coming to realize that their aspirations require a break with reformism and an inevitable confrontation with the bourgeoisie.

It is grotesque to reject “on principle” participation in a particular type of election or post. As long as the masses place their hopes in elections to executive posts, we must seek to participate in them and guide them through this stage of their political awakening. And if the workers elect us and demand that we fight in this post, we must do it! Not as reformists who adapt to the posts and not to comfort workers’ illusions but to make the clearest possible case that a gradualist road to the conquest of power is blocked by the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie and its state machinery.

Simply put, and what has been repudiated, is that the purpose of the revolutionary party is to guide the working class toward revolution. Comrades pondering if we can or cannot run for or take this or that executive post in general must stop posing the question in such an idealist way (and I am speaking here of all executive posts, including chief of police, judge, etc.). The method that consists in entangling the party in rigid and abstract dogmas, whose sole practical effect is to cut ourselves off from the movements of the masses, is typical of tiny, isolated organizations that have become comfortable in their position. It is petty bourgeois through and through.

As long as we are not strong enough to do away with executive posts—that is, as long as we are not strong enough to establish a workers government—we must work within these reactionary institutions and engage with the workers on that terrain. Otherwise, we are nothing but windbags.

Dialectical Relationship Between Principles and Political Struggles

The method of the Spartacist article is a rejection of dialectical materialism. However, one could argue that the most frontal attack on the Marxist method is not so much the position of refusing to run for executive posts but the way we gave birth to a new “principle.” The article states:

“Our earlier practice [of running for executive posts] conformed to that of the Comintern and Fourth International. This does not mean that we acted in an unprincipled way in the past: the principle had never been recognized as such either by our forebears or by ourselves. Programs do evolve, as new issues arise and we critically scrutinize the work of our revolutionary predecessors.”

Against the Internationalist Group (IG), which denounced the concoction of this “principle” and defended our past practice, we argue:

“In following the practice of our revolutionary forebears, our previous position was not subjectively unprincipled. But the IG’s continuing defense of such campaigns is unprincipled.”

So, we are to believe that the line between principled and unprincipled action in the electoral realm is…a motion at the 2007 ICL International Conference. From the moment this motion is adopted, the principle is “recognized” and anyone who does not abide by it betrays Marxism. As for our past practice, as well as that of the entire Marxist movement before 2007, it was not “subjectively unprincipled” (maybe it was “objectively” unprincipled?) because the motion had not yet been adopted!

It is true that “programs do evolve.” But not according to motions voted by tiny organizations which suddenly recognize principles when they appear in their heads. Programs and principles evolve with the development of the class struggle. The birth of the proletariat was the precondition for the birth of scientific socialism. The 1848 revolutions showed the need for the independent party of the proletariat. The Paris Commune gave rise to the understanding that the proletariat needs to break up the existing state and create its own. The First World War marked the era of imperialism and the need for a split with social-chauvinism. And so on and so forth through the Russian Revolution and its degeneration to the birth of deformed workers states and capitalist counterrevolutions, etc.

What was the groundbreaking development in the class struggle that led us to codify that running for executive offices had become incompatible with the proletarian revolution? The question was not even posed in these terms. Ditto for the position we had previously held.

Marxist principles are condensed lessons of the victories and defeats of the revolutionary proletariat. They are, by definition, abstractions which must constantly be applied to the realities of the struggle of the working class at a given juncture in order to guide the actions of the vanguard. In turn, the workers cannot be won to Marxism unless they come to see its principles as vital for the conduct of their struggles and the advancement of their interests. An inseparable dialectical relationship ties the principles of Marxism to the class struggle. As Trotsky wrote in “Sectarianism, Centrism, and the Fourth International” (October 1935):

“Though he may swear by Marxism in every sentence, the sectarian is the direct negation of dialectical materialism, which takes experience as its point of departure and always returns to it. A sectarian does not understand the dialectical action and reaction between a finished program and a living—that is to say, imperfect and unfinished—mass struggle.”

This brilliant remark precisely captures our former method. Starting from correct principles—the nature of the capitalist state and Marx’s lesson from the Paris Commune—that method completely rejects and brands as reformism the need to engage in the “imperfect and unfinished mass struggle” in order to fight for these principles. Instead, only the finished program matters, and in the name of not fueling illusions in the capitalist state, we dictate that Marxists must withdraw from elections for its executive posts. The practical result is to leave this field to bourgeois and reformist forces, which in turn guarantees the continued prevalence and even the strengthening of the illusions we claim to oppose. This is nothing but the liquidation of the revolutionary party.

We certainly tried to drape this scholasticism in Marxist language. For example, here is how we posed the issue in the opening lines of the article:

“Behind the question of running for executive office stands the fundamental counterposition between reformism and Marxism: Can the proletariat use bourgeois democracy and the bourgeois state to achieve a peaceful transition to socialism? Or, rather, must the proletariat smash the old state machinery, and in its place create a new state to impose its own class rule—the dictatorship of the proletariat—to suppress and expropriate the capitalist exploiters?”

Anyone who loses sight of the fundamental point might be lured by such a display of orthodoxy. Who could contest such ABCs of Marxism? But this collection of orthodox formulations only serves to obscure the fundamental point regarding the “question of running for executive office”: that before the proletariat can establish its own dictatorship, it must first be broken from reformism! Instead of the dialectical process connecting these two questions—that is, instead of posing the problem as breaking the working class from reformism and winning it to Marxism—the article presents two motionless objects, put side by side and never to clash with each other.

To summarize in the simplest terms: one cannot separate the principle that parliamentarism must be replaced by soviet power from the struggle to win over the working class to this understanding. Anyone who severs the relationship between principles and political struggle is condemned to vegetate in isolation.

This applies as well to the position taken in 2019 that it was unprincipled for revolutionaries to run for the European Parliament (see Spartacist No. 66, Spring 2020). On the contrary, as long as there are illusions in the European Union, Marxists must conduct revolutionary work within its parliament, aiming to prepare the working class to disperse that reactionary institution.

How Are Bourgeois Democratic Illusions Broken?

What exactly does the Spartacist article recommend that revolutionaries do? At best, it argues that we can run for legislative posts and have parliamentarians as oppositionists. But the article’s method would sabotage any serious campaign for legislative posts, too, by ignoring the central task of fighting illusions in bourgeois democracy as well as the need to guide the working class, starting from its own experience and offering a way forward for its immediate struggles. Just consider what our candidate’s response would be to the simplest question of all: “What would you do differently if you were in government?” “Oh! We do not take executive posts, thank you. After soviet power is established however….” No worker would take that seriously.

Elections to executive posts often receive the most attention from working people and generate the most illusions (like presidential elections in France, Mexico, the U.S., etc.). Yet the article proposes doing absolutely nothing but writing propaganda, or at best giving critical support to others while noting that running in these elections is unprincipled. Absurdity aside, the conception of politics behind this is profoundly anti-Marxist.

Illusions in bourgeois democracy, or in any other bourgeois ideology for that matter, are not broken through propaganda and theory. While those are essential to consolidate our party, not a single revolutionary organization in the history of class society has ever acquired a serious following with these alone. Masses are won in action, and they shed their illusions through great events and their own experience. For the working class to lose faith in bourgeois democracy requires a crisis of great magnitude that brings to the fore the conflict between its most burning and immediate needs and the existing political and economic order. The various mechanisms of bourgeois society, which in between crises can dampen this class conflict, are suddenly put under tremendous pressure by the objective situation, provoking the masses’ entrance into the political arena and their rapid changes in consciousness.

Even in such circumstances, experience shows that consciousness does not evolve in line with the objective situation. It is worth quoting at length what Trotsky wrote in the Preface to his History of the Russian Revolution (1930):

“The swift changes of mass views and moods in an epoch of revolution thus derive, not from the flexibility and mobility of man’s mind, but just the opposite, from its deep conservatism. The chronic lag of ideas and relations behind new objective conditions, right up to the moment when the latter crash over people in the form of a catastrophe, is what creates in a period of revolution that leaping movement of ideas and passions which seems to the police mind a mere result of the activities of ‘demagogues.’

“The masses go into a revolution not with a prepared plan of social reconstruction, but with a sharp feeling that they cannot endure the old régime. Only the guiding layers of a class have a political program, and even this still requires the test of events, and the approval of the masses. The fundamental political process of the revolution thus consists in the gradual comprehension by a class of the problems arising from the social crisis—the active orientation of the masses by a method of successive approximations. The different stages of a revolutionary process, certified by a change of parties in which the more extreme always supersedes the less, express the growing pressure to the left of the masses—so long as the swing of the movement does not run into objective obstacles.”

The masses enter the political scene not with a prepared plan but with the certainty that the current regime cannot go on. They acquire a growing understanding of the crisis through experiencing sharp shocks. Parties and leaders are put to the test; the movement to the left by the masses happens through successive approximations.

It is almost a law of history that in every serious crisis, the mass of workers pushes the existing system to its extreme limit by trying to use the old state machinery for their own purposes. From the Provisional Government in Russia in February 1917 and the 1918 SPD-USPD coalition in Germany to the popular fronts in France, Spain, Chile and elsewhere and Attlee’s Labour government: all these were brought to power by the working class believing that they were clearing the road to socialism through seizing the capitalist state. This is an all but inevitable stage in the political awakening of the masses.

The challenge for the revolutionary party is not to label these various attempts as reformist dead ends and then say “we told you so” when the proletariat gets crushed. Any dilettante can do this from his desk. The real challenge, and what is necessary, is to help the working class go through this experience in a way that can strengthen its position and advance a rupture with reformism.

This requires the ability to use all available weapons to exacerbate the fundamental contradiction between what needs to be done to solve the crisis—the independent struggle of the working class toward the expropriation of the bourgeoisie—and what is blocking its achievement—the existing consciousness and leadership of the workers movement. This problem can be resolved only through the course of struggle, through practical experience. What is required is a leadership which sees its perspective validated by the test of events, thus gaining authority among the workers, and pushes the masses’ prejudices to the point where they shatter on the objective needs of the situation. This is the key element distinguishing the Russian experience from all the others.

The method of saddling the party with so-called principles that reject in advance the use of this or that weapon in the struggle against the bourgeoisie is one that understands nothing of the dynamics of the class struggle and the fight for communist leadership. Running for executive offices and taking such posts is one of the weapons the revolutionary party must learn to use.

This approach is crucial not only in periods of revolutionary crisis. The eruption of acute crisis brings to the fore leaders and parties prepared by the entire preceding period. In reactionary and stagnant times, the revolutionary party must be able to make the best use of every experience, however modest, to train its cadres, engage in common work and political battle with contending organizations, get inside the class struggle and begin planting roots in the advanced layers of the working-class movement. A party chaining itself to abstract propaganda and pseudo-radical dogma isolated from the class struggle will be swept away at the first shock. This was our method, which was tested in March 2020 with the pandemic, and we all know the result: we collapsed.

Yes, Communists Can Assume Executive Posts

Comrade Jim Robertson, who first proposed that we reject running for executive offices in 2004, posed the question by saying that in such elections “you can talk to people, but already talking to people, saying ‘I want to be president of American imperialism but make it better,’ has its problems.” A pillar of the anti-Marxist method behind our approach was the idea that “assuming executive office or gaining control of a bourgeois legislature or municipal council, either independently or in coalition, requires taking responsibility for the administration of the machinery of the capitalist state,” as the Spartacist article put it. In other words, if the state is capitalist, then anyone elected to a post of responsibility becomes a capitalist politician. The logic is pure formalism. Suddenly, the class struggle and what the revolutionary vanguard does disappears into a simplistic mathematical equation.

The view that the only possible campaign for executive office is one that says “I want to make imperialism better,” and that the only way to assume such office is to run the capitalist state machinery and take responsibility for it, is premised on rejecting the class struggle as the decisive factor and liquidating the revolutionary party. It is perfectly possible to do what generations of revolutionaries before us have done and run a campaign telling workers: “I am running for president (or mayor, or any other executive post). What our party wants is to nationalize all major industries and banks, disband the police and army and arm the workers, end imperialism and have the workers instead of the capitalists run the country from top to bottom and enjoy the fruits of their labor. However, we know that the capitalist class will never let us do this and will put up strong resistance. That is why our movement can only succeed if workers are mobilized and ready to fight for their own power against the capitalist class.”

There is nothing reformist in this. It does not mean that if we win we will administer capitalism—it means exactly the opposite. To campaign in such a manner is the only way to meet the workers where they are and confront their illusions head-on. Consider the alternative: “We run in this election, but we will not take the post,” which is just another way to say: “Vote for me, but if I win, I am not going to fight.” Can you imagine if we would actually win an election and our first act in office would be to…quit!? This would bring irredeemable damage and discredit to our party and deliver the workers to the reformists.

James P. Cannon’s Socialism on Trial (Pathfinder Press, 1970), consisting of his testimony in the 1941 trial of 28 Trotskyist and Minneapolis Teamsters leaders, offers an excellent example of how to pedagogically explain to workers what we want, how we seek to get it and why they need to establish their own state. Cannon explained:

“When we say that it is an illusion to expect that we can effect the social transformation by parliamentary action, that doesn’t mean that we don’t want to do it, or that we wouldn’t gladly accept such a method. We don’t believe, on the basis of our knowledge of history, and on the basis of our knowledge of the greed and rapacity of the American ruling class, that they will permit that kind of solution.”

Was Cannon here, or anywhere else in his testimony, speaking of taking responsibility for administering capitalism? Of course not. He explained what sort of transformation is necessary to liberate the working class and said that while we would be happy if that happened through bourgeois democracy, history has shown that the ruling class will not leave the scene without a fight. In the hypothetical scenario where a revolutionary party is elected to the presidency, revolutionaries would, in Cannon’s words, do what Lincoln did to the slaveholders: “Lincoln took what he could and recruited some more and gave them a fight, and I always thought it was a wonderfully good idea.” Only a hopeless formalist could think that this simple and popular explanation is reformist.

Revolutionaries and Municipalities

The chance of a revolutionary party capturing the presidency seems so remote that it is easy to dismiss. The same cannot be said of municipalities, in which communists (not only Stalinists and reformists but actual revolutionaries) have been elected in the past. It is not inconceivable that a somewhat small party with modest roots in the workers movement would win a majority in a locality. What to do then? Again, we must start with the struggle against prevailing illusions. The traditional illusion in this field is municipal socialism, that is, the idea that socialism can be gradually introduced by taking over municipalities and using those positions to create “socialist” bubbles by enacting petty social measures.

The Spartacist article noted Point 13 of the “Theses on the Communist Parties and Parliamentarism,” adopted by the Second Comintern Congress in 1920, which stated:

“Should Communists hold a majority in institutions of local government, they must (a) organize revolutionary opposition against the central bourgeois government; (b) do everything possible to serve the poorer sectors of the population (economic measures, creating or attempting to create an armed workers’ militia, and so forth); (c) at every opportunity point out how the bourgeois state blocks truly major changes; (d) on this basis develop vigorous revolutionary propaganda, never fearing conflict with the state; (e) under certain conditions, replace municipal governments with local workers’ councils. In other words, all of the Communists’ activity in local government must be a part of the general work of undermining the capitalist system.”

—published in John Riddell, ed., Workers of the World and Oppressed Peoples, Unite! Proceedings and Documents of the Second Congress, 1920 (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1991)

I believe this is excellent. Contrary to the spurious claims of our article, this was not municipal socialism; it was its direct opposite. The purpose of Point 13 was to guide the actions of communists to best demonstrate the bankruptcy of municipal socialism and use such posts to show the need for workers to take power on a national level.

The purpose of the Theses, which our article characterizes as a “contradictory hodgepodge that licensed ministerialism” (!), was precisely to draw a line against both the opportunist Second International, whose parliamentarians adapted to bourgeois society and acted as vulgar lackeys of the capitalists, and the ultraleft anti-parliamentarians who, in reaction to the Second International’s betrayals, rejected all forms of parliamentary activity. Trotsky’s preamble to the Theses proclaimed: “The old, accommodationist parliamentarism is being replaced by the new parliamentarism, which is a tool for the destruction of parliamentarism in general.” The question is not to choose between opportunist parliamentarism and rejection of all parliamentary activity but to participate in the parliamentary struggle as revolutionaries.

Point 13 was not written in a vacuum. Nor was it part of “anti-Marxist amendments” watering down the original Theses, as our article claims. It was drawn from the experience of the Bolsheviks themselves, who campaigned in local municipalities between February and October 1917. Lenin’s “They Have Forgotten the Main Thing” (May 1917) was one of multiple articles written at the time regarding the Bolsheviks’ platform for municipal elections. He wrote:

“Foremost in this platform, topping the list of reforms, there must be, as a basic condition for their actual realisation, the following three fundamental points:

- No support for the imperialist war (either in the form of support for the war loan, or in any other form).

- No support to the capitalist government.

- No reinstatement of the police, which must be replaced by a people’s militia.

“Unless attention is focused on these cardinal questions, unless it is shown that all municipal reforms are contingent upon them, the municipal programme inevitably becomes (at best) a pious wish.”

Lenin’s intention was to expose the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries, who proposed all sorts of reforms but whose treacherous position on these three points was a fundamental obstacle to their realization. He insisted in particular on the third point, arguing for the need to disband the police and create a people’s militia. In other words, he instructed communists who obtained a majority in municipalities to use their posts to advance the break with the reformists and to turn these positions into working-class bastions in order to facilitate the attainment of state power by the soviets.

In contrast, our view was that any parliamentary activity in the sphere of executive posts could only be reformist. This is true only if one thinks that once elected, we, communists, would enter the mayor’s office and run the local state machinery, with its encrusted bureaucracy, police thugs, petty regulations and scarce budget, and try to do the best for poor people in this framework. Yes, in that case, the so-called communist mayor would become a bourgeois mayor: an administrator of scarcity and a lackey of the central government.

But the issue becomes completely different and new possibilities open up if one refuses to be confined to the bounds of private property. Instead of viewing executive posts from the standpoint of administrating the local state machinery, communists would rely on organizing and mobilizing the workers movement, allied with the poor petty bourgeoisie and the unemployed. Then it becomes clear that we would run for such posts on a clear revolutionary platform that tells the working class what we intend to do and what cannot be done short of state power. It becomes obvious that we would not administer local capitalism but would seek to build organs of dual power and mobilize the working class against the bourgeoisie, that we would not run the local police but would work to disband this institution.

Many comrades get stuck on the scenario of being elected the head of a municipality in a situation that is not revolutionary, wondering how we would deal with this or that issue without falling into reformism. This is not a dialectical way to approach the question because it is entirely speculative. I believe it reflects our near-zero experience in the mass movement.

Posing the problem that way necessarily means ignoring a thousand other factors that are impossible to predict—the social, economic and political context locally, nationally and internationally; the depth of the class struggle; our own roots and authority in the workers movement; the situation of the ruling class. All these elements and more are key to evaluating the relationship of forces, what is possible or not and, crucially, how a revolutionary party would get into office.

My answer to the hypothetical scenario above is: we will fight for our program, just like we would anywhere else, with the methods of the class struggle. We would do our best to guide and strengthen the proletariat while undermining its reformist illusions under the conditions imposed on us.

Preparing for Battle

The ICL did not inherit a problem unresolved by our movement, as the Spartacist article claimed. The fact that the Comintern, Lenin, Trotsky, Cannon and many others did not make a fundamental distinction between executive and legislative offices was no grand discovery of ours. Our forebears simply did not view the question through such a formalistic lens. To ponder over the separation of powers, to pick and choose which terrain to wage battle on or which tool to use is something they did not have the luxury of doing and a method they wholeheartedly rejected.

The Bolsheviks declared war on bourgeois society in its entirety and understood that the battle had to be brought into all spheres of social life. Communists elected to parliament or to head municipalities, to trade-union offices, cooperatives, workers militias or any other posts of responsibility, were expected to fight for communism and act accordingly under the discipline of the party, period.

The Bolsheviks understood that the actions of the revolutionary party had to be based not on abstractions but on the requirements of the class struggle. They understood the need for the party to link itself with the working-class movement and to remain flexible in all situations, able to adapt to what is needed for the final goal. They sought to teach aspiring revolutionaries that the role of the party was to guide the proletariat at every stage of its political consciousness, making use of its experience to educate it in the bankruptcy of reformism and the necessity of the dictatorship of the proletariat. That is what our party must learn to do for the battles ahead, and that is why we must be ruthless with regard to our past.