https://iclfi.org/pubs/rb/2/hawke-keating

The following article by SL/A Central Committee member, C. Cunningham is based on discussions resulting from the 2024 SL/A and B-L Fusion Conference. It follows the document “How the Whitlam government paved the way for neoliberalism,” published in Red Battler No. 1.

The reality confronting the Whitlam, Fraser and later Hawke/Keating governments was that Australia’s highly protected and outdated industrial base (what Keating would later call Australia’s “industrial museum”), having been hit by a series of external shocks, was internationally unviable and uncompetitive. By the early 1980s Australia had faced a decade of recessions. Industries were failing, inflation was high, bankruptcies and unemployment were on the increase. This was given extra gravitas as governments around the world, most notably Thatcher’s Britain and Reagan’s United States, had already begun to implement neoliberal economic “shock therapy” to maximise international competitiveness by reducing costs and increasing productivity through savage attacks on the organised working class. If nothing changed, Australian capitalism would be left in the mud and its people would become, as Singapore’s then PM Lee Kuan Yew put it, the “poor white trash of Asia.” Australia’s capitalist rulers had to urgently deregulate and modernise the economy.

But the route for the Australian ruling class to push through neoliberal reforms on the model of Reagan and Thatcher would not be easy. Firstly, there was a deeply entrenched, centralised wage indexation system that would have to be torn down. But more fundamentally what stood in the way of the bourgeoisie was the power of a highly organised and economically militant proletariat. For well over a decade leading up to Labor leader Bob Hawke’s election in 1983, unions in Australia had been able to consistently bring industries to a standstill, pushing back against half-measure attempts to restrain wages and reorganise the economy. While the situation never came close to dual power, it was an ongoing on-again-off-again struggle between the bourgeoisie and the working class over which class should call the shots. The longer this went on the greater the pressures became, deepening and deepening the crisis.

In May 2019, following Hawke’s death, former secretary of the Australian Treasury, Ken Henry, spoke to the dangers for the bourgeoisie laid bare by this crisis: “The centralised wage indexation system that we had was so rigid that opening the economy up—and being able to do it in a way that didn’t completely traumatise the economy and society—that was the biggest challenge…” It was clear that the working class of Australia was not going to give up its wages and conditions without a fight. But then, under the Hawke and Keating governments, it seemingly did. Henry continues, “Hawke managed to keep the support of the trade union movement, while overseeing the dismantling of this giant piece of machinery that they were once the masters of.” Even in hindsight, almost forty years later, such an outcome is seen by the bourgeoisie as miraculous, “a stroke of genius.” And with good reason!

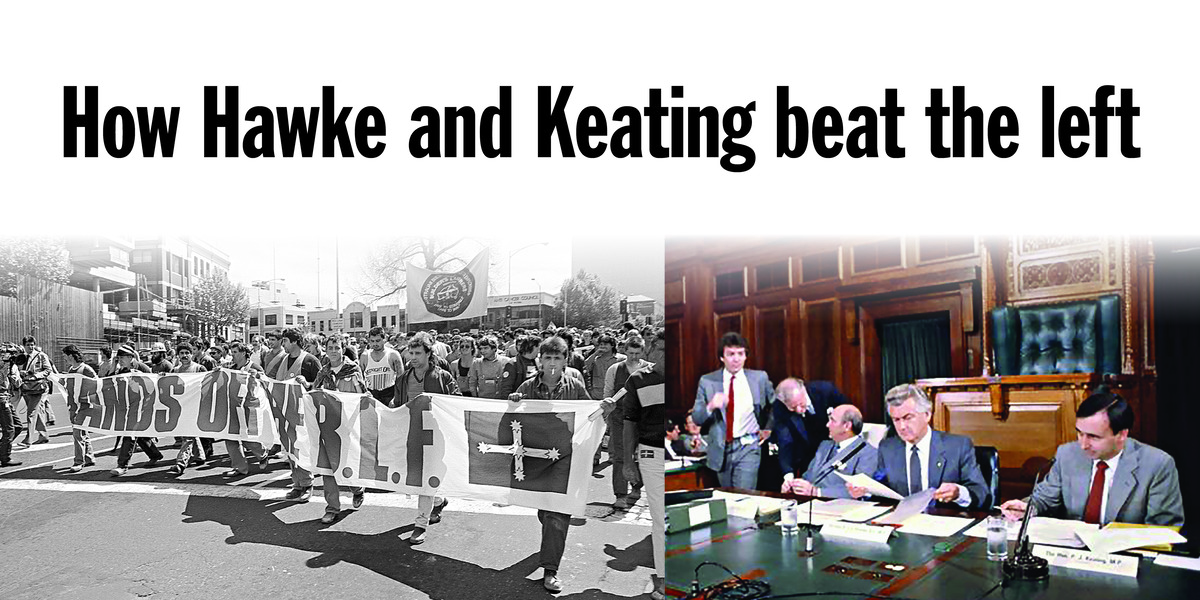

By gaining the consent of the union movement, Hawke and Keating were able to neuter and ultimately gut this “giant piece of machinery.” The union bureaucracy became the key backers of the Hawke/Keating program. Crucially, among them were “left” union bureaucrats such as prominent Communist Party (CPA) supporter Laurie Carmichael, who had been instrumental in the 1969 general strike that freed tramways union leader Clarrie O’Shea from prison and who regularly brought production to a halt. The minority who attempted to defy Hawke and Keating, such as the Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) and the pilots’ union, were isolated and smashed.

By 1996 workers had suffered 13 years of “shock therapy” under Hawke/Keating rule. Wages were stagnating, the unions were enfeebled and whole swathes of the working class were leaving them. Once heavily unionised mainstays were being gutted, publicly owned companies were being privatised, while manufacturing was being slashed. Unable to trace an independent path forward, much of the left had shrivelled or, like the CPA, outright dissolved. The economy had been restructured in the interests of the ruling class and the basis of Australia’s modern liberal order had been bedded down.

The Accords: unions commit harakari

So how did this come to be? In 1979 as president of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), and positioning himself to be the leader of the Labor Party, Hawke, in a lecture titled “The Resolution of Conflict” pointed to the crisis of Australian capitalism, darkly warning:

“Australia stands poised on the threshold of the 1980s more divided within itself, more uncertain of the future, more prone to internal conflict, than at any other period in its history.”

Indeed. By 1981-82 Australia was experiencing its fifth recession in ten years and massive working-class unrest. At the same time, there was a growing weariness and despondency among workers who recognised that despite years of militancy their livelihoods were going downhill. Clearly in spite of the combativeness of the working class, left Laborite trade-union militancy was incapable of solving the crisis that wracked Australian capitalism. In fact, it only exacerbated and deepened it. Workers were increasingly looking for a solution to the standoff.

Two paths were posed. Either the bourgeoisie would take complete charge and reorganise the economy in their interests or the working class would. But standing in the way of the latter was the Laborite bureaucracy shackling the workers movement. Their pro-capitalist program left them balancing between the interests of the capitalists and of the workers. This ensured that at this critical moment they served only to tie the working class to a neoliberal transformation of the economy that was fundamentally against the proletariat’s interests. Urgently needed was a leadership that could demonstrate this and break workers from this doomed course. However, no group offered such a leadership.

The ruling class could have attempted to resolve the crisis with a boots-and-all savage crackdown against the working class and its organisations. But such a course would have posed significant risks for the bourgeoisie, potentially inflaming an already combustible situation. One could not predict where that might lead. Instead, the solution for the capitalists was provided by the newly elected Labor prime minister. By the time of the 1983 federal election, Hawke had spent years using his deep connections in the labour movement to bring about “national reconciliation” and develop a political solution for the bourgeoisie.

Working with treasurer Paul Keating and ACTU head Bill Kelty, Hawke’s solution came in the form of “consensus-based” Prices and Incomes Accords. These were no-strike agreements, which neutered union power by chaining the unions to the government in the service of the capitalist rulers. Their aim was to suppress wages to reduce inflation and to end industrial conflict so the economy could be restructured unencumbered by proletarian opposition. The whole project was premised on the lie that the two main classes could happily go forward together in the interests of the nation to the mutual benefit of all.

Once elected, Hawke immediately called a national summit between bosses, union leaders and government in which the first Accord was rubber-stamped. Under it, the unions agreed to accept real wage cuts in return for a so-called “social wage.” This included two key pillars, a supposedly universal healthcare system in the form of Medicare and the promise of an employer-paid national superannuation scheme. These reforms were packaged up with a neoliberal economic program to, in the words of Kelty, “open up the economy to the rest of the world, increase productivity, [and] promote competition.” It wouldn’t take long before industrial disputes decreased, the bosses’ profits increased and the unions began haemorrhaging.

So why would a traditionally very organised, powerful and militant union movement voluntarily comply with measures that were clearly designed to throttle union activity and scupper their role as the economic defence organisations of the working class? The answer by most of the left did not go beyond regurgitating the line that Hawke gained union support for his neoliberal program as part of a trade-off for the “social wage.” For instance Socialist Action, the predecessor of Socialist Alternative and Solidarity, argued that the “social wage” on offer didn’t nearly compensate for the attacks and so the unions should never have agreed to the Accords.

But such arguments, which don’t go beyond a program for more militant trade-union struggle to secure greater reforms, disappear the main issue. A real crisis was confronting Australian capitalism and the key reforms underpinning the so-called “social wage,” while offering some benefits to workers, were in fact completely within the framework of the neoliberal transformation of the Australian economy in the interests of the capitalist rulers and international finance capital. Never counterposing to this transformation a working-class political solution, the union misleaders could only fight for a “fairer” neoliberalism. The reformist left, instead of exposing the bureaucracy’s role, tailed its “left” wing, at best trying to pressure them to see what a “bad deal” was offered by the Accords.

Left Laborite betrayal

To understand why and how such a betrayal took place it is necessary to understand the social position of the union bureaucracy and its role. As Leon Trotsky observed in his unfinished 1940 work “Trade Unions in the Epoch of Imperialist Decay”:

“…imperialist capitalism can tolerate (i.e., up to a certain time) a reformist bureaucracy only if the latter serves directly as a petty but active stockholder of its imperialist enterprises, of its plans and programmes within the country as well as on the world arena.”

To maintain the positions that their privileges derive from, the Laborite bureaucracy must prove themselves indispensable agents for the ruling class within the workers movement. This was sharply posed in the lead-up to Hawke’s election. For years these bureaucrats had waged economic struggles against a ruling class whose system was in crisis without ever challenging the foundations of that system or offering a political way forward for their working-class base. Instead, they hammered away with strikes and protests to curb capital’s excesses while peddling the Laborite myth that workers and their rulers had a shared national interest and with just enough counterpressure the system could be made to work for all classes. But over the preceding decade this Laborite militancy had not advanced the “national interests” of Australian capitalism but helped push it to the brink.

To continue its existence, Australian capitalism desperately needed to drive down workers’ conditions and reorganise the economy, a task these unions were increasingly standing in the way of. It was against this backdrop that the spectre of Thatcher and Reagan-style union-busting was raised. The union bureaucracy was trapped in a hopeless situation. If they didn’t surrender the bosses would move to break the backs of their unions which would mean losing their positions, jail-time or worse. But open surrender would be intolerable to their working-class base who had fought tooth and nail for decades. In this context, Hawke’s Accords appeared as a godsend. These reforms were the consummation of all that the union tops believed in and had fought for in their days of militancy. For them, as for Hawke and Keating, this deal (Accords plus social wage) was proof positive that by improving the prospects of capitalism the working class could get their fair share. This came with the bonus that there would be no need to go into the trenches to get it. Crisis resolved.

Not only would these union leaders be tolerated, they would be lauded for helping rescue an ailing system. By participating in the Accords they would get a big seat at the government table, exchanging pleasantries with and influencing legislators. At last, after all their travail, they would be at the helm helping steer the good ship of capitalism in the interests of working people. Or at least that was the fairy tale they told themselves and the working class. Carmichael even went so far as to describe the Accords as “a transitional program for socialism.” Of course, the opposite was true. Unable to put forward an independent solution in the interests of the proletariat, the union bureaucracy could only reconcile the working class to the bourgeoisie’s neoliberal transformation of Australian capitalism. The working class’s striving to improve its livelihood was not channelled against this liberal order but subordinated to it. Emblematic of this process were the lefts’ iconic “social wage” reforms.

The Superannuation Guarantee (SG) is the sharpest example. It was spun by the ALP and left bureaucrats as an unalloyed progressive reform in which compulsory employer contributions would support workers in retirement while building up a future national savings plan to finance local industry and infrastructure development in a then capital-starved country. A key aim of this scheme was in fact to reduce the welfare bill by transferring the government’s former responsibility to provide modest retirement benefits to a completely individualised, privately managed scheme supplemented by an increasingly rundown pension system. In many ways, this reform perfectly reflected the Laborite goals and outlook of the Hawke/Keating government and union bureaucracy. SG was designed to become a massive slush fund for giant asset management firms to speculate with on the stock market, giving finance capital a boost while also tying workers’ retirement benefits to the fortunes of international finance capital. Even for the upper layers of the working class who were able to develop a “nest egg,” their retirement plan was completely contingent on the success of Australian capitalism.

As for Medicare, which the Laborite leaders spruiked as a universal healthcare system and a great advance for public health, it was no such thing. To be sure it provided free public hospital and emergency treatment. In the early days it also provided mostly free consults with private General Practitioners (GPs) who were subsidised by the system. These benefits were not to be sniffled at. However, far from being a universal national healthcare system, Medicare excluded many areas of healthcare. Furthermore, subsidies to GPs and the whole system were paid for by a levy on workers’ wages over and above their income tax. Whatever benefits fell to workers, far from overhauling the public system, Medicare actually helped entrench private delivery of healthcare while doing nothing to improve and expand the drastically underfunded and crumbling public healthcare system, such that today private medical insurance is increasingly necessary.

It is true that some, including an upper layer of workers, gained some material benefit in the short to medium term from these reforms and from Australian capitalism being extracted from its malaise. However, this came at the price of completely enslaving the proletariat to the ruling class’s interests at a critical moment. The betrayal by the union bureaucracy, including the crucial role played by the left bureaucrats in selling the Accords to their militant base, ensured the capitalist rulers a free hand to move forward with their plans to develop a new model of unfettered capitalist rule in which, as Keating put it, “increasing the profit share was the name of the game.” The result was the devastation of many sections of the proletariat and an overall deterioration of the position of the working class. This process, where the union tops truly began sawing off their own legs, would ultimately redound on the left and labour movement emboldening the bosses to wage more and greater attacks.

The handcuffing of the unions to the state while opening up the economy to international competition had a self-reinforcing dynamic. The power of international finance capital in the economy grew as the power of the organised labour movement decreased. The government began their economic “reforms” by floating the Australian dollar and deregulating the banks. By 1988 they had put forward a massive phased reduction in tariffs. As tariff walls came down, uncompetitive industries were closed, leaving tens of thousands of workers in manufacturing, textiles and other industries out of work. The result of this was not a “more competitive” local industry as Hawke, Keating and Kelty projected but a decimated one. Formerly protected industries were shuttered wholesale, the industries shielded were ones that couldn’t simply pack up and leave such as mining and agriculture. The Australian economy became increasingly parasitic while tightening its bonds to US finance capital which under Reagan was undertaking a similar process.

Blackmail, threats, state repression

This reorganisation of the economy was not a seamless process. It required the continued support of the workers movement especially as attacks escalated. While the union bureaucrats were fraternising with their patrons in the halls of (capitalist) power, workers who had initially supported the Accords were continually confronted with the new reality of Hawke and Keating’s Australia. Disillusionment was beginning to grow in the proletariat against the deceptions peddled by the bureaucracy that the Accords were a “transitional program for socialism” or similar lies. This was particularly true for a broad stratum of workers, living precariously from pay cheque to pay cheque, including the likes of the BLF. For the Hawke/Keating program to succeed these workers needed to either be marshalled back into line or isolated and smashed.

Government blackmail and threats played a crucial role in keeping restive workers in line. Workers were told that if they challenged the Accords and went on strike, they would destroy the new economy and the country would quickly fall back into crisis. This time, the government warned, the crisis would be terminal, leaving everyone to suffer an impoverished future. This included the veiled threat that if the unions no longer conformed, they would all suffer the savage treatment Margaret Thatcher had dished out to British workers. Reinforcing Hawke’s earlier fears of Australia becoming the “white trash of Asia,” in 1986 Keating warned that Australia would become a “banana republic” unless workers continued to make sacrifices under the Accords. At this time, facing a significant drop in the price of commodities, Keating declared:

“…if we don’t make it now we never will make it. If the government cannot get the [economic] adjustment, get manufacturing going again and keep moderate wage outcomes and a sensible economic policy, then Australia is basically done for. We will just end up being a third-rate economy.”

—Keating, Kerry O’Brien (2015)

Reflecting the very real weaknesses of capitalist Australia, Keating’s “banana republic” comments nearly crashed the economy. The government demanded the working class pay. An austerity budget was announced, promised tax breaks for workers were binned and union leaders agreed to further wage restraint. It was in the context of these threats and cuts that the government moved decisively to extract what Keating called the “rotten teeth” of the union movement by crushing and deregistering the militant BLF for defying the Accords by fighting for higher wages. Three years later the government would defeat the pilot union’s wage push by using the air force to replace striking pilots.

The smashing of these unions exemplified how crucial maintaining the Accords was to the legitimacy of the Labor government. Without the success of this pact, they had nothing to offer the ruling class and would be done for. That is why taking on the Accords meant going smack up against the most powerful forces in the country, including the Labor government, the Labor-loyal ACTU leadership, the left union bureaucrats and the capitalist state. The attack on the BLF was a watershed moment for the labour movement. The situation cried out for revolutionary leadership. Had the attack become a spark for broader working-class struggles, breaking the stranglehold of the Accords on the labour movement, then the whole course and development of the country could have changed.

Smashing of the BLF

At the time the government brought the hammer down against the BLF, workers were increasingly confronted with falling living standards. Textile and manufacturing workers across the country were beginning to lose their jobs as industries closed. As for the BLF base, they saw their livelihoods diminish as their wages fell and the bosses’ profits soared. Harking back to the old-school union militancy of the ’70s, these workers demanded wage increases as part of gaining their “slice of the pie.” Under pressure from the base, the BLF leadership under federal secretary Norm Gallagher, having initially supported the Accords, decided to defy them.

But this defiance was based not on a class-wide fight against the Hawke/Keating government but on the BLF’s traditional guerrilla tactics of applying bans and carrying out militant actions on individual building sites. There was, however, no going back to the militant trade unionism of the ’60s and ’70s which had brought the country to a stalemate. Defying the Accords represented an existential threat to the Labor government. They could not simply ignore and accede to a “rogue union” acting outside the Accords. For both parties it was do or die. Openly defying the bourgeoisie, without any intention or plan to defeat them, meant Gallagher’s strategy was not only doomed but an adventure which gave the ruling class an avenue to crush the union.

What was required was not a return to the BLF’s Laborite militancy but a break from it—to demonstrate this to the working class was the key task of revolutionary leadership. It was only through exposing how Hawke and Keating’s Accords were crucial to resolving the crisis of Australian capitalism, that Gallagher’s futile attempts to be an “exception” could be laid bare. Furthermore, to break from the isolation that the BLF faced, they needed to tap into the widespread sympathy of the broader layers of the working class. Defending workers’ jobs and conditions from encroaching attacks, let alone winning new gains meant going directly up against the interests of the ruling class; not reminiscing about the protectionism of yesteryear but confronting the whole neoliberal reorganisation underway. What needed to be put forward was a program to reorganise the economy in the interests of the proletariat that could defend, expand and modernise the productive forces of Australia’s industries. This could only be realised through the expropriation, collectivisation and planning of industry under working-class rule, which, in turn could only come about through a social overturn of capitalist property relations.

Failure of the left

Defending the BLF required demonstrating to the working class the bankruptcy of not just Hawke and Keating but the union bureaucracy as a whole—especially that of the BLF. However, the left failed on all counts. From the beginning most socialist groups from the CPA, to the predecessors of today’s Socialist Alternative, Solidarity, Socialist Equality Party and Socialist Alliance tailed Hawke and applauded his successful bid for government. These groups avidly clung to the “left” union bureaucrats, even as they corralled the working class behind Hawke’s Accords. If they didn’t follow key elements of the CPA in supporting the smashing of the BLF, many left groups tailed Gallagher’s guerrilla strategy to the very end. These groups argued for greater militancy and for other unions to defend the BLF and defy the Accords. But unable to put forward a political strategy for victory counterposed to the BLF leadership, their defence of the BLF amounted to little more than sidestepping the necessary class-wide fight against the bosses. If realised their strategy could only have emboldened the government in its crackdown.

Others who denounced the Hawke/Keating regime and all wings of the union bureaucracy were still unable to trace a path forwards for the working class and motivate a break with its Laborite misleaders. This camp included the SL/A’s predecessor, the SL/ANZ. While the SL/ANZ was correct to denounce the Labor government and their union brethren, it was unable to expose their bankruptcy or fight to break workers from these Laborite chains. Take for instance the Accords. The SL/ANZ savagely denounced them but its criticisms didn’t go beyond abstractly excoriating class collaboration and Laborism while sloganeering for revolution. What the SL/ANZ didn’t do was take on the bureaucrats’ political justifications for the Accords and their central purpose in resolving the crisis of Australian capitalism. Hence, the SL/ANZ was unable to effectively challenge the union bureaucracy and the arguments they used to shackle the proletariat to the Hawke/Keating government. It never once took on the government’s blackmail and was reduced to shrill denunciations and criticisms abstracted from the ongoing struggles.

The attack on the BLF highlighted this. It was imperative for revolutionaries to take on the BLF leadership’s guerrilla tactics and expose their futility. The BLF tops were widely known as Maoists. Despite that left posture, they were not looking to defeat the Accords (let alone the ruling class!), but to be a successful outlier in an otherwise strangled labour movement. The SL/ANZ, who had a small BLF fraction on the ground, were correct in attempting to address these questions. These militants waged some principled struggles to defend the union, including when the bureaucrats were throwing in the towel. They were also correct to emphasise the need for an industry-wide and even class-wide fight to defend the BLF and bust the Accords.

But to break BLF members from their support to Gallagher’s old-school Laborite militancy required proving that a return to the ’70s era class stalemate could not be tolerated by the bosses. The preceding period was one of crisis, which left Laborite militancy only deepened. By the ’80s such militancy meant putting yourself up against the core interests of the ruling class. The BLF leadership’s fatuous perspective that they could be successful going it alone against the Accords, instead of fighting for class-wide action to smash them and take on the ruling class, was not only doomed from the get-go but set the union up for complete destruction.

For a class-wide fight to succeed it was necessary to win over workers outside the BLF—especially those in the BWIU whose leadership was spearheading the destruction of the BLF by joining Hawke and Keating’s witchhunt and poaching members. Winning these workers required driving a wedge between the working-class base and the pro-Accord tops of the unions, politically taking on the Accords and the blackmail which kept large numbers of workers tied to their leadership and the Hawke/Keating program. What needed to be put forward was a counterposed political solution, a workers’ reorganisation of the country under a planned economy which would build up and modernise Australia’s crumbling industries. Such a perspective could also have won broad layers of disgruntled and increasingly impoverished workers (those who were beginning to abandon Labor and the unions in droves) and direct their frustrations in a progressive direction against the Accords and in defence of the BLF and union movement as a whole.

Instead, the SL/ANZ responded to Hawke and Keating’s reforms with timeless formulas about the bankruptcy of Laborism, not once taking on the fundamental arguments which kept workers in thrall to the Labor government. In fact, following the election of Hawke, the SL/ANZ attempted to explain away working-class allegiance to Labor with apocryphal references to the Australian proletariat’s “national character” as being hopelessly racist and Laborite. This included going so far as to argue that “shattering the insular chauvinist complacency of this remote island continent” and breaking workers from Laborism rested solely on external shocks such as “the military defeat and humiliation of the Australian ruling class in a counterrevolutionary war in Asia or economic catastrophe” (“Against White Australia ‘Socialism’” ASp No. 104, Summer 1983/84). The fight for revolution became not one of leadership but a waiting game for better objective circumstances.

It was in this arid framework that the SL/ANZ substituted the necessary head-on argument against the Accords with empty denunciations of Laborite anti-Sovietism. Of course, it was imperative to fight against the US-led anti-Soviet war drive as an integral part of advancing the workers movement in Australia. But abstractly grafting such denunciations onto the unfolding struggle on the Australian terrain amounted to moral preaching about defending the Soviet Union. Ironically, substituting the necessary arguments against the Accords with empty denunciations of the anti-Soviet war drive weakened the SL/ANZ’s capacity to break the working class from their misleaders, many of whom supported the Hawke-backed US-led war drive. Ultimately, in spite of all the turmoil and division within the workers movement, in the absence of a revolutionary pole, the proletariat remained wedded to its Laborite leadership. This not only led to the BLF being smashed but gave the Labor government impetus to continue its “shock therapy” and restructure the economy in the bosses’ interests.

The result was catastrophic. In the years following the deregistration of the BLF, the Labor government continued to turn the screws on the working class while facing less and less resistance. By 1991, in the face of double-digit unemployment and interest rates—the worst recession since the Great Depression—Keating could nonchalantly declare that this was “a recession that Australia had to have.” Such a statement made by a Labor prime minister only 20 years earlier would have meant all hell breaking loose. However, as a testament to the weakened state of the labour movement these comments were met without protest. Hawke and Keating lorded over not just the corpse of the BLF (and later the pilots’ union) but a workers movement in stranglehold. By the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the balance of class forces, both in Australia and internationally, had shifted decisively in favour of imperialism.

Australia’s liberal order and its ruin

The US-led imperialist victory over the Soviet Union was a dream come true for the Australian ruling class. It had long hitched its wagon to the American Empire, which was now not just the premier imperialist power but the unchallenged hegemon over the entire world. In Australia, this compounded the already historic defeats suffered under the Labor government and their union bureaucracy.

Now under a hegemonic US-led world order, Australian capitalism’s strategy became to extend and entrench this order at home and abroad. The ideological justification was one of liberal triumphalism: that the “end of history” had been reached and that liberal capitalism was the only road forwards. This ideology was embraced and promoted by the Labor government and the union bureaucracy. Internationally, under now prime minister Keating, Australian capitalism pushed to “enmesh” with Asia: i.e., to foster economic liberalisation for the purpose of deepening imperialist penetration throughout the region. Thus, the Labor government was in the forefront of championing the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum which promoted greater free trade in Southeast Asia under American auspices.

Domestically, Keating made it clear that the only good union was one that totally submitted to government diktats and embraced the “national interest” of Australia’s liberal order. By late 1991 he was able, without opposition, to introduce a system of enterprise bargaining which buttressed the Accords and increased productivity (read exploitation) by outlawing industry-wide struggles. During this period, Keating embarked on a mass union-busting privatisation spree—selling off Qantas, the Commonwealth Bank, the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, Australian National Lines etc. These formerly public companies were gleefully snapped up at fire sale prices by gigantic, predominantly US-run investment and asset funds.

The result of Hawke and Keating’s reforms wasn’t the “modernisation of Australia’s industry” or to “get manufacturing going” but a further brake on the development of Australia’s productive forces, a decline in its industrial capacity and an overall hollowing out of what became an increasingly parasitic economy. Becoming little more than a “quarry with a view,” the Australian economy increasingly intertwined itself with, and relied on the success of, American finance capital. American capital became dominant over many Australian companies and banks. In turn, Australia’s limited investment capacities, if they were not outright funnelled back into Wall Street, were coupled with American investments overseas. It was through this that Australian capitalism’s rentier nature was deepened and a growing seal of parasitism was set on the whole country. The only thing that prevented Australian capitalism from completely falling into this abyss was the mining industry, which by that time was beginning to rapidly expand. But even this was reliant on the success of American finance capital and its penetration into China.

While Hawke and Keating’s measures afforded the Australian liberal order relative prosperity for thirty years, the ultimate result has been a significantly more hollowed out and vulnerable economy built on a foundation of sand. Today, Australian capitalism again approaches crisis. To keep itself afloat the ruling class needs to join with its American big brother in tearing down the very liberal order they had built and prospered from (see “Australia at a crossroads,”). It is imperative to assimilate the lessons of how we got here and why the left and organised working class is a shell of its former self in order to rebuild anew. When once again crisis reaches Australia’s shores, the question will be posed: will it be resolved in the interests of the capitalists or the proletariat? For the latter to succeed what is required is a ruthless struggle to break the working class from all wings of the Laborite misleadership that has brought the workers movement to its decrepit presentday state.